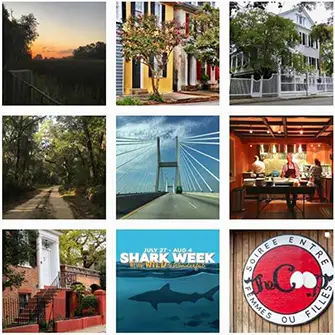

101 Bull Street

On Bull Street traveling towards the Ashley River, several townhouses tend to capture people's attention. Sarah Smith built these Italianate-style row houses, starting with the one she lived in at 101 Bull Street, around 1853-1854. "Row houses" refer to a row of houses where each house shares a common wall with the next.

For purposes of this post, we will focus on 101 Bull Street. The façade can be misleading; 101 Bull has over 6,000 square feet. Look at the ornamentation above the door. If you're from Charleston or visit frequently, this heavy terra cotta ornamentation will look familiar because of its resemblance to the window cornices at the Mills House Hotel at 115 Meeting Street.

The original Mills House Hotel was constructed at the same time as 101 Bull and the adjoining row houses and was built in the same Italianate style. The hotel’s original terra cotta window cornices were made in Worchester, Massachusetts; perhaps the exterior ornamentation on the row houses came from the same place. (Please note that the original Mills House Hotel was demolished in 1966 and reconstructed as the present hotel; the present window cornices are fiberglass reproductions).

The group of row houses starting with 101 Bull Street is known as “Bee’s Row,” receiving this name during the Civil War. William C. Bee and Co., which was established in the 1840’s as a rice and cotton brokerage in Charleston, expanded its business during the Civil War to become a major seller of blockade goods. As the Civil War progressed, the Federal gun range increased substantially due to advances in siege artillery, and the Bee company moved to these Italianate row houses so it could sell its goods in an area of the city outside the range of the Union cannon. People could visit the “Bee Store” to purchase various items such as shoes, fabric, etc, but don’t think the blockade runners were only bringing in necessities – I inherited two European porcelain dishes that were brought in through the Union blockade of Charleston (and later buried in the backyard when it became obvious the South would lose the war).

Blockade running was big business, but dangerous. However, many considered the high risks worth the high payoff. The retail business of the Charleston merchants depended on the blockade runners, and the merchants were willing to pay for their businesses to succeed. The merchants even organized to offer gold bounties up to $100,000 in gold on the Union blockade ships. Those blockade runners who were paid in Confederate currency obviously did not fare well at the end of the war, but those who only ran the blockade for payment in gold were some of the few individuals who were wealthy after the war ended.

Next week we will continue to explore Charleston history through her places and people.